Artists spread paint over a canvas; pastry chefs mix flour and sugar. As a programmer, your medium is text.

Specifically, plain text, devoid of any fonts, colors, or formatting of any kind—just letters, numbers, symbols and spaces, in the buff. And, when you're talking about source code or data, it's always displayed in fonts that make every character the same width.

You’ll find that programmers are so into plain text, we use it for everything (like our shopping lists, journals, etc.). I'm even writing this post in a plain text editor!

What's the appeal? Why are we so adamant about it?

There are plenty of paeans to plain text out there; a couple of my favorites are Derek Sivers's Write Plain Text and and the "Power Of Plain Text" section of The Pragmatic Programmer by Andrew Hunt and David Thomas.

But I felt like there was a little more to say about why programmers specifically are so bullish on plain text.

Why Programmers Love Plain Text

1: There’s Nothing Hidden

When you’re working with plain text, what you see is all there is1. Everything in a file is explicit, right in the surface.

Compare that to, say, a formatted document like in Google Docs or your email, where everything is not visible. For example, some words might be hyperlinks. You can’t tell from looking at that hyperlink what it points to unless you take some other action (clicking it, editing it, etc.)

This can be important because when something isn’t doing what you expect, you need to see right away what’s actually there.

Now, even in plain text, some characters are still invisible (like spaces and line breaks). But they still take up the same amount of space2, which is another reason why fixed-width fonts are used.

2: Patterns Are Easier To Spot

Plain text (in a fixed-width font) makes it easier to see regularities (and discontinuities) in text; all the columns of letters line up vertically, and the same number of characters always takes up the same amount of space.

This means, for example, that you can tell at a glance whether a group of lines is indented the same amount, or whether one letter in a column of words is different from all the rest.

Our eyes pick up visual patterns like this easily (line detection, similarity detection, figure versus ground) because that's just part of walking around without bumping into things. And this makes it much faster to parse text, because the first round of visual processing happens at a sufficiently shallow level of semantic depth; recognizing patterns, rather than reading (and understanding) words.

3: Seeing What Changed Is Easy

In software, you change things all the time. Your goal is to make things better, but sometimes you make things worse. In either case, you often want to see exactly what changed between two versions of something.

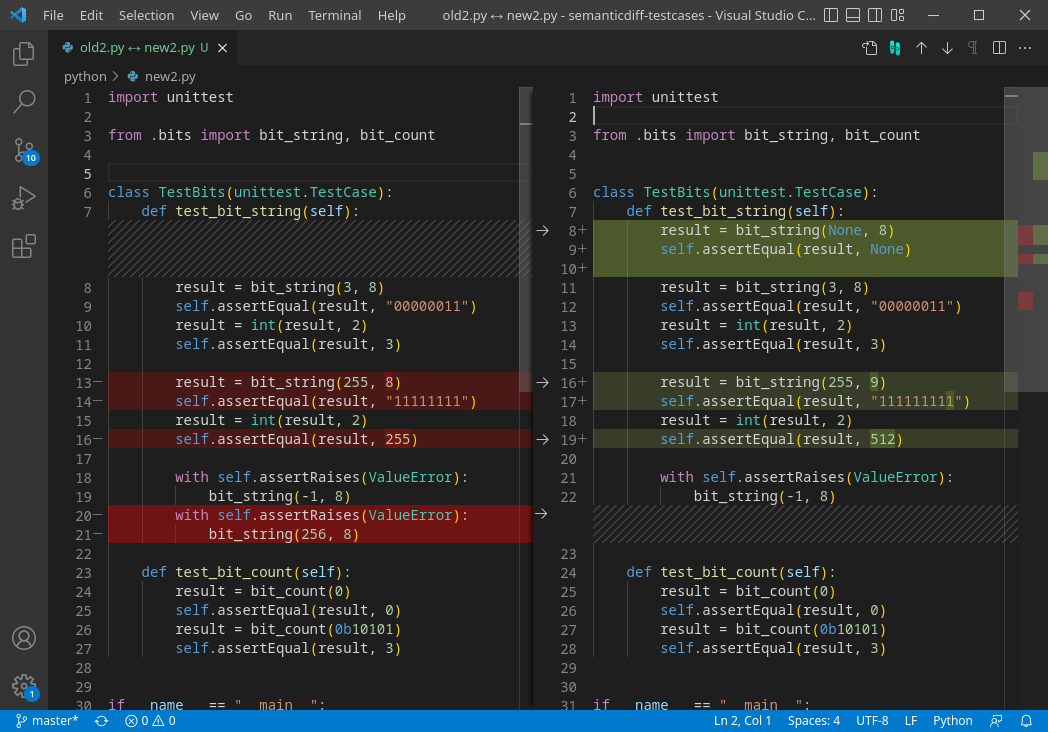

In plain text, this is easy. We call this a “diff” (for “difference”) and it looks like this:

You can see that some lines (8-10) were added, and others were just changed (like how the number in line 16 changed from 255 to 512).

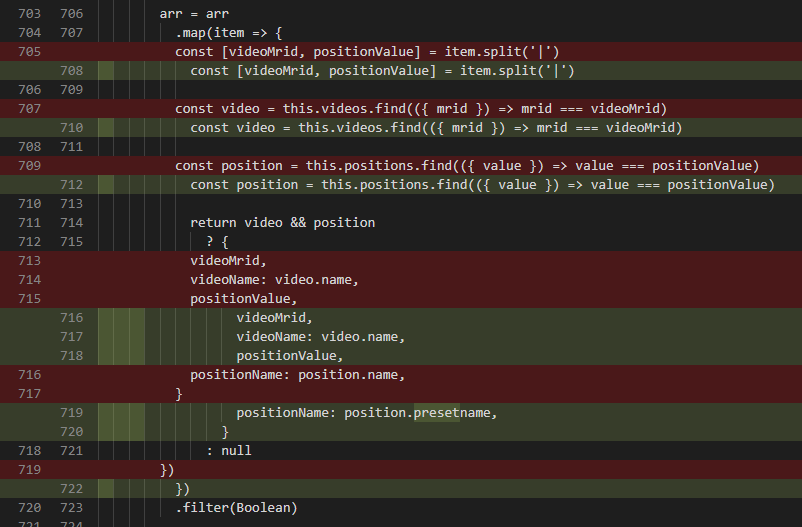

You can also show diffs side by side, which is more intuitive in some cases:

Notice here how easy it is to see that the only thing that changed was indentation!

Because nothing is hidden, a diff shows exactly what changed, even if it is just spaces or capitalization or whatever. Diffing wouldn’t work if text could have other formatting, like bold or italics or fonts.

4: Maniuplating Text Is Fast

Have you ever tried to adjust the width of a table in a Word or Google doc, only to send the whole document into a horrible cattywumpus state? Have you ever spent precious minutes trying to copy and paste just the right bits of text from one place to another?

That kind of thing is just much easier in plain text; what you select and move is simple and obvious. Advanced text users (and most programmers would count themselves as “advanced text users”) learn to do things with extreme efficiency, using keyboard shortcuts to minimize their keystrokes and rapidly do things like:

- move forward or back, a word or line at a time

- change a whole block of text (capitalize, sort lines alphabetically, etc.)

- flip the order of words or lines

If you hear programmers talking about their undying love vim or emacs3, a big part of it is this efficiency with text manipulation. In vim, you can do crazy stuff with just a few keystrokes, like:

ci"— "change inside quotes." Your cursor is somewhere inside a quoted string, you hit these three keys, and the contents vanish while leaving the quotes intact, with you in insert mode ready to type the replacement. There's alsoci(,ci{,ci[for parentheses, braces, brackets.dt.— "delete till period." Deletes everything from your cursor up to (but not including) the next period. Thetmotion ("till") works with any character.ggVG=— Go to the top of the file (gg), start visual line mode (V), go to the bottom (G), and auto-indent everything (=). Four keystrokes to fix the indentation of an entire file.

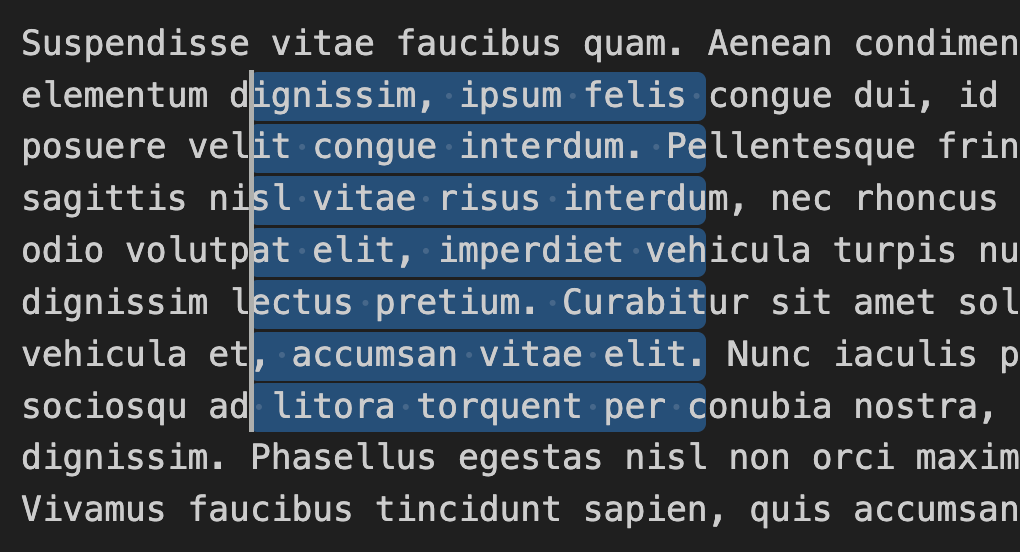

Learning vim or emacs is a big task, and probably not something you'd do if you weren't a full time programmer. But even common text editors often have little tricks up their sleeve; for example, in VSCode (a common, free programming IDE) there's a keyboard shortcut (option+shift+drag) you can use to make a "rectangular" or "non-contiguous" selection

This is incredibly useful for doing things like quickly changing one character in every line a huge file. And only possible because of plain text.

5: It’s Durable

Plain text is the same everywhere, on every computer, in every country4. It’s been the same since the 70s, and it will be the same when the earth is consumed by the heat death of the sun.

If you store some data in Google Docs, you’ll be able to access it forever! Er, I mean, until Google goes out of business. As Andrew Hunt and David Thomas put it in The Pragmatic Programmer:

Human readable forms of data, and self-describing data, will outline all other forms of data and the applications that created them. Period.

So if you store data in plain text, your disembodied brain will still be able to access it as you travel at near light speed through the outer reaches of the galaxy. Plain text is in it for the long haul.

6: It's Universal

All the low-level tools on every operating system (Mac, Windows, Linux, etc) all speak plain text; in particular, the Unix mindset (and thus the underlying Mac mindset) uses text as the interface to nearly everything. And because of this, text goes in and out of every single tool seamlessly.

Similarly, web APIs and internet protocols largely speak plain text. It's a big wide wooly world out there, so plain texts acts as a lowest common denominator. Again, in the words of The Pragmatic Programmer:

In fact, in heterogeneous environments the advantages of plain text can outweigh all of the drawbacks. You need to ensure that all parties can communicate using a common standard. Plain text is the standard.

The only things that don’t use plain text, at this point, usually only deviate because they need to eke out extreme performance (like the internal representation in a database, or software that streams and plays video). Computers are so fast now that it rarely makes a difference, even in these cases, so text is usually the best first bet.

7: Bonus: LLMs Eat Text For Breakfast

Finally, plain text has one other really nice property, which is that it’s what Large Language Models use. When they’re trained, each possible plain text word is turned into one or more “tokens” (which you can think of as word parts or stems, like "break" and "fast" for "breakfast"). Internally, the LLM is actually working with numbers (each token is assigned to a random integer so they're all the same length); but on the outside, it's all plain text, all the time. Even when you see them give you tables and headings back, it's because they're outputting and rendering markdown (which we'll cover in a minute)5.

This means that whatever you're doing, if you can do it in plain text, LLMs are much better at doing things with it. If LLMs are the fire, text is the fuel.

Text File Formats

But … what if you want formatting? What if you want other structure in the text? There’s no inherent structure in a plain text file, but are also a handful of other common text file formats you should be familiar with so you're not confused when you encounter them. Let’s cover the most common ones: markdown, csv, json, yaml, and html.

1: Markdown

Markdown is the simplest "text plus" format. It's really just text with a few simple symbols that control formatting, and it's super easy:

# This is a top level heading!

This snippet shows you how markdown works.

## Here's a second-level heading

In this paragraph, we've got some **bold text**, *italic text*, and `inline code`.

[This is a link](https://example.com)

> This is a blockquote

- Unordered list item

- Another item

1. Ordered list item

2. Another item

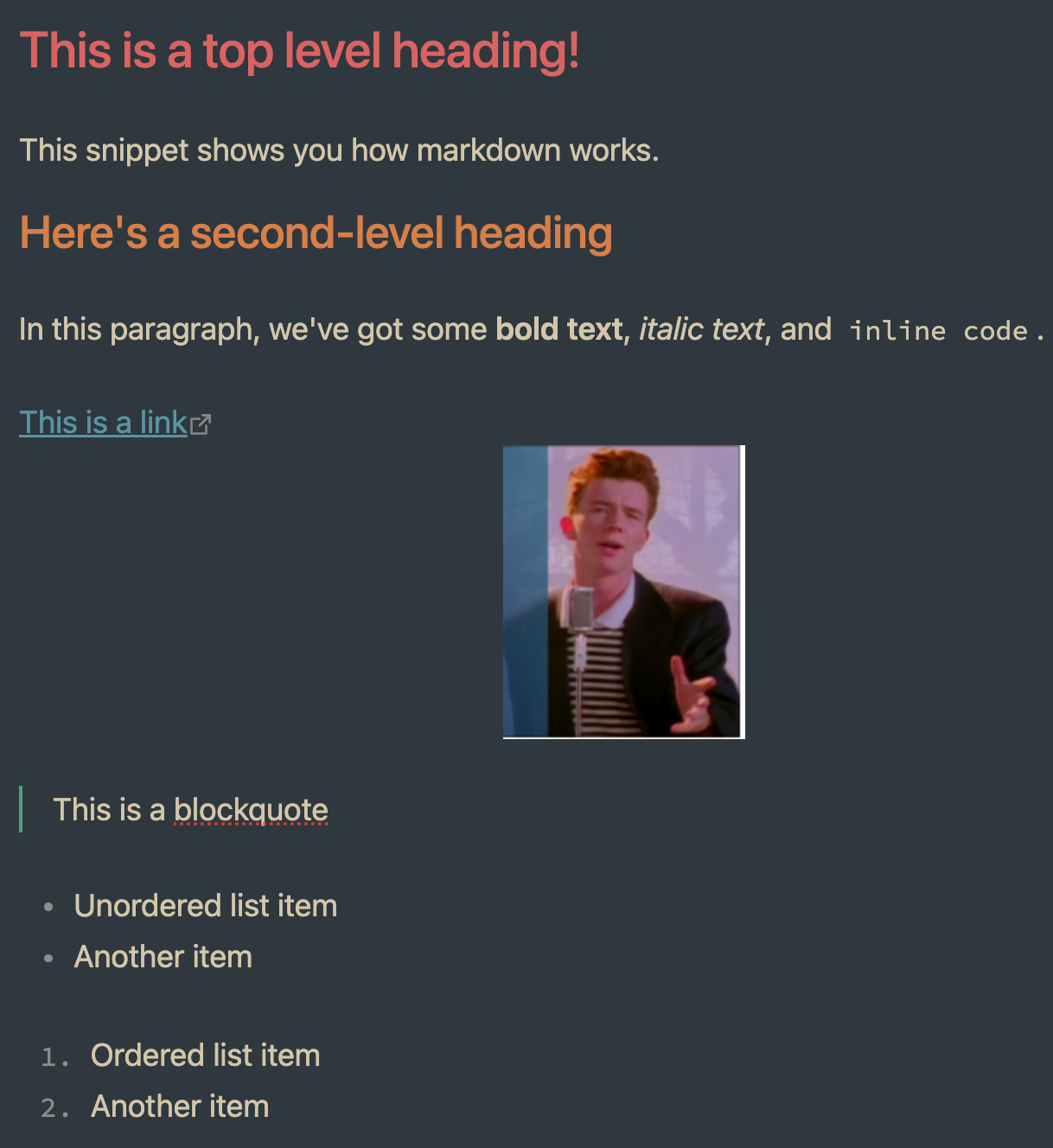

And this looks like:

There are a few more things you can do (like tables) but really, not many! What you see is all there is.

There are bunches of tools (like VS Code) that can "render" markdown (i.e. show it to you with the actual formatting rather than the symbols). But markdown is delightful precisely because you almost don't even need to render it; it reads just fine as-is. You get the best of both worlds: nice formatting when you want it, but with a "real" underlying form that's just plain text (and thus can be stored anywhere, examined, diffed, etc.).

Markdown is something you'll find yourself hand-writing sometimes, but it's also something LLMs love to generate.

2: CSV: Comma Separated Values

Also in the "so simple you shouldn't be scared of it" category is a "csv" file, which stands for "comma-separated values". It consists of ... wait for it ... values separated by commas:

name,age,role,hair_color,catchphrase

Homer Simpson,39,Safety Inspector,bald,D'oh!

Marge Simpson,36,Homemaker,blue,Hmmmm

Bart Simpson,10,Student,yellow,Eat my shorts!

Lisa Simpson,8,Student,yellow,If anyone wants me I'll be in my room

Maggie Simpson,1,Baby,yellow,*suck suck*

Ned Flanders,60,Store Owner,brown,Hi-diddly-ho!

Mr. Burns,104,CEO,white,Excellent

This is basically a spreadsheet hiding in text form; the first line has the headers, and each row has exactly the same number of "cells", where a comma indicates the cell boundary. Things get a little more squirrely if you have to support commas IN the values6, at which point you might put the values in quotes:

"Mr. Burns","104","CEO","white","Excellent, Smithers"

But that's really about it. CSV is a simple, compact way to represent tabular (spreadsheet-like) data, and LLMs love it, so you'll see it all the time.

3: JSON: Javascript Object Notation

This one starts to get a little more complicated, but it's very common (and insanely useful) so you should get the hang of it.

Going back to our csv example, what if you wanted to capture something where each character had more than one of something? Like, say, favorite foods or personality traits? That'd be a pain in the ass to shove into the csv. So we do this instead:

{

"characters": [

{

"name": "Marge Simpson",

"age": 36,

"role": "Homemaker",

"hair_color": "blue",

"catchphrase": "Hmmmm",

"favorite_foods": ["pork chops", "casserole", "coffee"],

"personality_traits": ["patient", "caring", "responsible", "moral"]

},

{

"name": "Bart Simpson",

"age": 10,

"role": "Student",

"hair_color": "yellow",

"catchphrase": "Eat my shorts!",

"favorite_foods": ["Krusty Burger", "Squishees", "candy"],

"personality_traits": ["mischievous", "rebellious", "clever", "underachiever"]

}

]

}

This is json, and it's a universal format for arbitrarily complex data:

- The curly braces

{}define objects (collections of key-value pairs) - The square braces

[]define arrays (ordered lists of values).

Key-value pairs have a "key" (the first bit in double quotes, which says what something is), and then a value (the bit after the colon, which can be words, numbers, etc).

JSON is cool because it's simple and readable (look how much easier it is to eyeball than that csv!), but also because values can also be objects and arrays; you can put arrays inside objects, objects inside arrays, and keep going as deep as you need. That's what makes it so flexible: with just these few simple rules, you can represent nearly any data structure imaginable, from a flat list of names to a deeply nested tree of relationships. CSVs can be converted into JSON, but the reverse isn't true, because csv doesn't allow nesting.

You might also notice that compared to the CSV, the JSON is quite verbose (because it has to repeat the headers over and over in each key, and has a bunch of whitespace like tabs and new lines). That makes it a bit less efficient. But remember: computers are really fast! So unless you're dealing with a lot of data, it usually doesn't matter much7.

You probably won't ever hand-write much JSON, because you don't need to; LLMs are very good at it. If you see curly braces, flying around, it's probably JSON.

4: YAML

This is a little bit more of a niche format, but you’ll also see it sometimes, so you should be aware of it. YAML stands for “Yet Another Markup Language” (see? Programmers are funny!), and it’s sort of like JSON without the curly braces and Square braces, using indentation to express the same thing:

characters:

- name: Marge Simpson

age: 36

role: Homemaker

hair_color: blue

catchphrase: Hmmmm

favorite_foods:

- pork chops

- casserole

- coffee

personality_traits:

- patient

- caring

- responsible

- moral

- name: Bart Simpson

age: 10

role: Student

hair_color: yellow

catchphrase: Eat my shorts!

favorite_foods:

- Krusty Burger

- Squishees

- candy

personality_traits:

- mischievous

- rebellious

- clever

- underachiever

If your brain isn’t used to parsing things with braces, this can look a lot more readable! The only special characters are colons and dashes.

Personally, I’m a big fan of YAML; it’s a little harder to parse for computers, but most of the time, the things were using it for, that’s no biggie. One place you might encounter it frequently is that actually, it’s legal for markdown files to start with a little chunk of YAML (called “front matter”).

5: HTML

Finally, I'll mention HTML, which stands for "Hyper Text Markup Language". It's what web pages are made of. Here's the same example above converted to html:

<h1>This is a top level heading!</h1>

<p>This snippet shows you how html works.</p>

<h2>Here's a second-level heading</h2>

<p>In this paragraph, we've got some <strong>bold text</strong>, <em>italic text</em>, and <code>inline code</code>.</p>

<a href="https://example.com">This is a link</a>

<img src="rick.jpg" alt="This is an image">

<blockquote>This is a blockquote</blockquote>

<ul>

<li>Unordered list item</li>

<li>Another item</li>

</ul>

<ol>

<li>Ordered list item</li>

<li>Another item</li>

</ol>

HTML serves the same purpose as markdown, but with a lot more features and complexity. It's also a lot less readable than markdown (especially with real world web sites, where the HTML gets a LOT more complex than this example).

You should basically never manually write HTML, and it shouldn't be the primary way of storing stuff where markdown is an option. HTML ends up being more like program source code, machine readable and human "kinda readable".

You may have also heard of another format called “XML“, which is short for “extensible markup language”8. XML is a little out of favor right now, because you can express much the same thing in JSON in a more efficient and readable format. But you will occasionally still see it, especially related to APIs.

Conclusion

So, there you go—a crash course in why plain text is the medium of programmers.

Sources

- Write Plain Text by Derek Sivers

- "The Power Of Plain Text" in The Pragmatic Programmer by Andrew Hunt and David Thomas.

Footnotes

1: With a nod to the delightful book by Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast And Slow, which used that phrase in a very different context.

2: Fun fact: not always. There’s a character called a “zero-width space” which takes up, well, zero space. Really! It exists so that long compound words can wrap between lines if they need to, without putting a dash or space in the word. This was never a good idea. If you want to see a programmer’s eye twitch, ask them about last time they ran into a zero-width space!

3: But NEVER both! It’s one of programmer-dom’s lasting holy wars.

4: This is a little bit of a lie; character encodings complicate this a bit, but it's mostly fine.

5: Some LLMs are multi-modal, meaning they also read and speak images; these are NOT plain text, obviously.

6: And still more squirrely if you need to have quotes and commas, at which point you have to "escape" the quotes inside the quotes, like "He says "Excellent, Smithers"".

7: Fun fact, there's a new-ish format called TOON, or token-oriented object notation, that's just a less token heavy version of json which is harder to read & write correctly, but more efficient for LLMs to use.

8: Starting with X instead of E because X is an inherently cooler letter than E … or at least, it used to be.